The dark subtexts of cricket literature

Why reading acclaimed works from decades ago is often revealing

Samir Chopra

07-Aug-2014

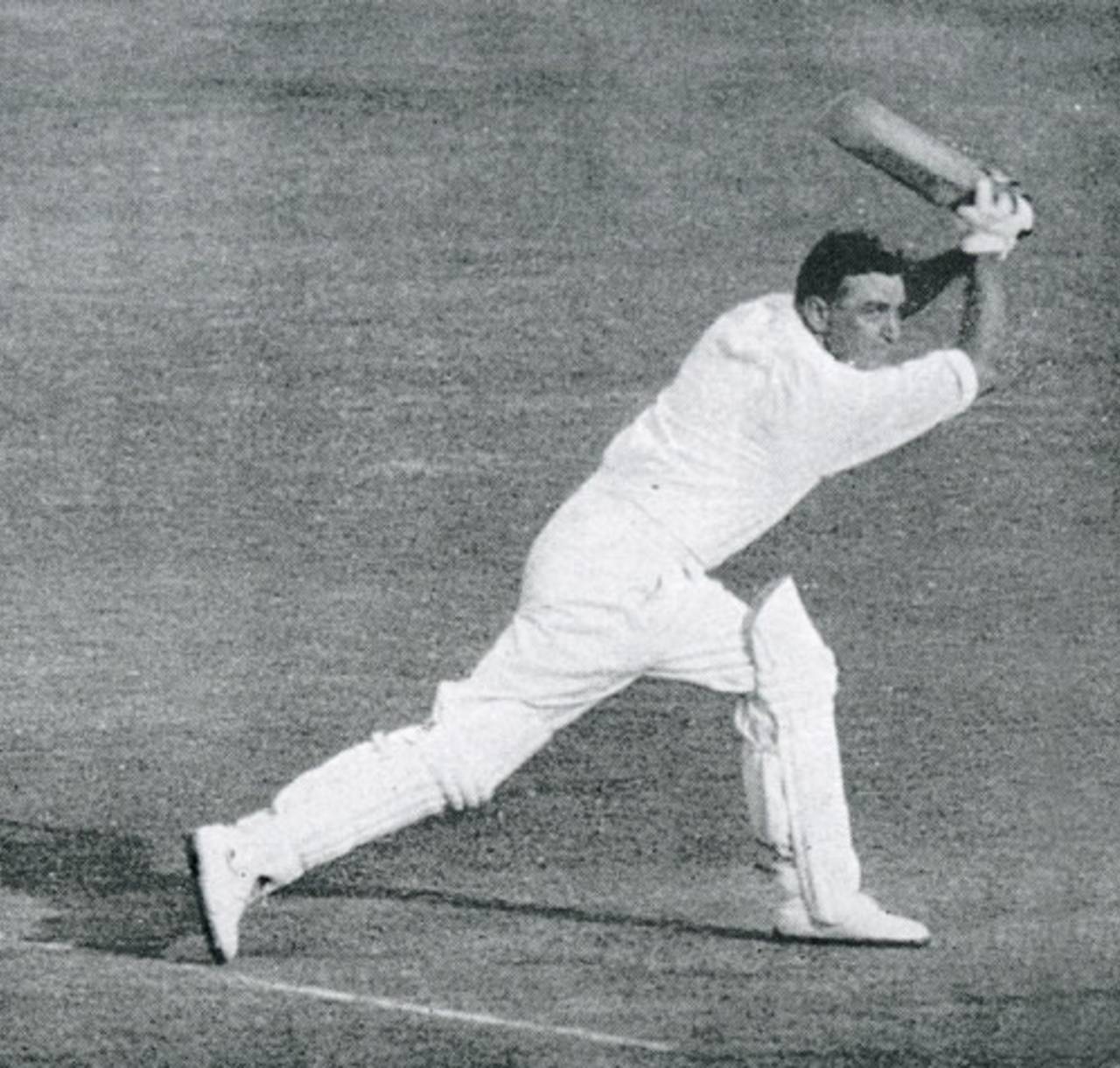

Wally Hammond: "imperial" • The Cricketer International

In a post here on the Cordon, a couple of years ago, noting my book-reading experiences as a youngster in India, I wrote:

Slowly, I moved through the denizens of Area Code 796.358, all in hardback, and which included, quite obviously, the usual suspects: Cardus, Swanton, Fingleton et al. This was the British Council library, and my mind was slowly attuned to a particular history with its particular narrative, its preferred locales, heroes and legends. As far as ideology-promulgating institutions go, the BCL was particularly successful: I grew up with a particular cricketing mythology central in my mind, one that would take some displacement.

I was reminded of that childhood and teen years reading experience as I read the excellent Picador Book of Cricket (ed. Ramachandra Guha). This post is not a comprehensive review by any means, but rather a very brief nod at one aspect of the acculturation provided by my reading experiences noted above.

Consider, for instance, the first section, titled "From Grace to Hutton", which, in dealing with great batsmen and bowlers - almost all, quite understandably, other than George Headley, English and Australian - of Test cricket's earliest days, till the post-war period, signals through its title that cricket's fons et origo and terminus alike are not just batsmen, but English ones at that. There is no disputing the accuracy of the description of the section's contents: the first essay describes the first English sporting teams, including cricketing ones, to go on tour; the second is CB Fry's technical description of WG Grace's batsmanship; the penultimate essay is Alan Ross' tribute to Len Hutton; the last selection is a poem in honor of Jack Hobbs.

In between, we find a rather interesting exhibit of cricketing semiotics in Ronald Mason's essay on Walter Hammond (excerpted from his 1955 Batsman's Paradise.) The essay is titled "Imperial Hammond" and the following passage, describing Hammond on the 1928-29 Ashes tour of Australia, in which he would score 905 runs, shows why:

On that tour he entered into possession of a kingdom for which, seasons before, he had begun to make insistent bids. I say 'kingdom' with considered stress on the word; about him and his cricket was a perennial air of cool domination… Hammond lorded it unabashed like an emperor… he seems to have been gifted with a modesty and charm which make his public character even more attractive… as a public figure he displayed the pride of a commander, a pride without frills and flounces, a direct and uncontradictable pride… when he came down the steps and out on to the grass, you could hear in your ears the trumpets and the drums of an imperial salutation. His very name sounded like a ceremonial discharge of cannon.

"Kingdom", "domination", "lorded", "emperor", "charm", "pride", "commander", "direct", "uncontradictable", "trumpets", "drums", "imperial salutation", "ceremonial", "cannon". Pity the poor postcolonial subject, only recently liberated, reading this verbal cavalcade. He might well wish to throw himself at the feet of anyone remotely associated with such a regal entity; he might indeed wish, all over again, to be subjected to his dominion, and continue to receive all manner of instruction - cricketing and moral alike.

A few pages later, we are treated to a description of Hammond's well-known brilliance at slip. His victim is the

very erratic and equally energetic Mushtaq Ali - a batsman of freedom and beauty whose charm was expansive and evanescent, like candy-floss.

There is that word "charm" again, but it is accompanied by "erratic", "energetic", "freedom", "beauty", "evanescent" and "candy-floss". This young man, all sweetness and softness, presumably gambolling about in the woods, displaying without a care in the world his liberated pulchitrude and resembling a sickly-sweet confection to be consumed by children on holiday at the beach, surely stood no chance against those who signal the firing of cannon with the mere utterance of their names?

Worth a closer look, too, is Donald Woods' 1982 essay on Abdul Qadir, in which we are told that we could:

Imagine that face emerging from the mystic gloom of a Karachi bazaar to whisper dread tidings of deceit in high places and intrigue in back streets, and the name Abdul is somehow appropriate, hinting at the mystery and magic that is about to be worked…

Such a moustached creature, muttering darkly about insufficient baksheesh for services rendered, and thus all too capable of slipping a retaliatory dreg of poison into his master's morning tea, unsurprisingly, on having an appeal denied by an umpire:

dances an angry tattoo upon the turf, jumping up and down and uttering fierce cries of the sort that surely terrified whole generations of marauders out of the Khyber Pass.

In these days and times there are many principled critiques that abound of the dreams of Big Data, but there are too, many advantages that may accrue to enhance our understanding of the phenomena so studied. One surely will be cricket literature. I look forward to the day when the various book scanning and digitising projects currently underway reach completion and we will be able to subject texts to a much closer examination of their many messages, visible and hidden.

Samir Chopra lives in Brooklyn and teaches Philosophy at the City University of New York. He tweets here