A systematic approach to bettering the DRS

Systems are about different components working in tandem towards a goal. Instead of aligning its components, the DRS pits the on-field umpires against technology and the third umpire

<b>Samir Srivastava</b>

10-Aug-2013

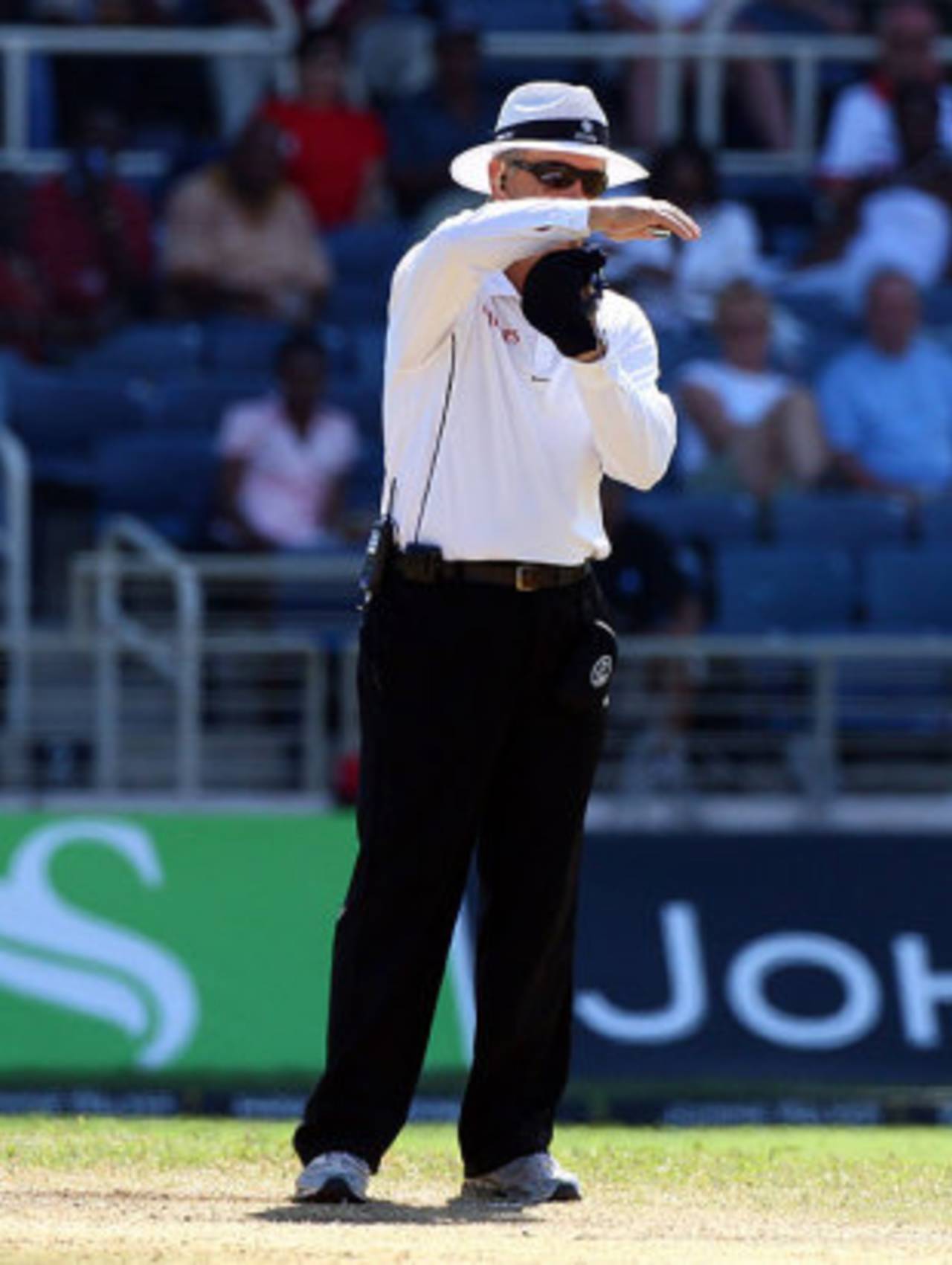

Instead of aligning its components, DRS pits the on-field umpires against technology and the third umpire • Getty Images

The chances of the Decision Review System (DRS) creating another major controversy during the current Ashes series seem greater than another Watson lbw dismissal. And going by the ICC's reaction, the chances of the DRS getting fixed any time soon look even more remote than Watson's waft getting a technical fix. The ICC got it right when it recognised that it was creating a decision-making "system". But it has been ignoring some critical aspects about systems when implementing the DRS.

Systems are about different components working in tandem towards a goal. Instead of aligning its components, the DRS pits the on-field umpires against technology and the third umpire. But first, we need to ask if the DRS is working towards a sensible goal. Should the DRS really be about eliminating howlers? At the elite level, an umpiring howler ought to be an exception. If it isn't, the problem lies elsewhere and throwing a multi-million dollar technological solution at it is not the answer. Surely any decision-making system should try to get as many decisions correct as possible but the desire to eliminate only a howler or two amounts to the DRS seeking very low hanging fruits.

Can the DRS aim for those elusive fruits at greater heights? If yes, at what cost? This brings us to another aspect about systems. It can be counterproductive to try to optimise all the components of a system. Usually, individual components within a system must work within themselves to optimise the whole system. Everyone seems to agree that we cannot get 100% of the decisions right all the time. The challenge therefore is to use DRS in a manner that minimises errors.

The errors are of only two types: a batsman is either declared out wrongly (the false positive decision) or wrongly declared not out (the false negative decision). The DRS can be optimised to almost entirely eliminate false positive decisions. An automatic review of all the out decisions, if implemented sensibly, would ensure this. Such a system would also eliminate the need to grant reviews to the batting team. For sanity to prevail, inconclusive replays should, at all times, result in the benefit of doubt going to the batsman (and not to the on-field umpires as happens currently). So no Hot Spot evidence would mean not out. Similarly, unless there was conclusive proof of a clean catch, the batsman would continue batting.

But what about borderline leg-before decisions? For instance, should a ball that is predicted to merely shave the bails win a positive verdict? The answer is yes, provided we were confident in the accuracy of the predictive paths. If the current technology leads to accurate predictive paths 93% of the time, the solution is to alter the dimensions of the stumps during TV replays by 7%. If a ball is then predicted to kiss the stumps, it would be a kiss of death.

As far as false negative decisions are concerned, the aim should be to reward the bowling team. They could therefore be granted two reviews for every hour of bowling on a non-cumulative basis - if not used within the set time, the two reviews would lapse and a new cycle would commence. Each unsuccessful review would still result in forfeiture, but only for the the hour, after which both reviews are restored. The on-field umpires should be at liberty to seek help from technology at any stage for any decision, however, the bowling team should continue to enjoy the right to seek a review, if only to feel reassured that they are not left completely at the mercy of the umpires' judgment. The suggested changes will lower error rates to an extent that they become a non-issue.

If the current error rates are in single digits, then is all this fuss over fixing the DRS justified? Some argue that the unfair false positive decisions received during the course of a batsman's career get balanced by the lucky false negative decisions they enjoy. But this logic completely ignores spectator sentiments. The spectators judge the DRS by its ability to produce a correct decision in the heat of a contest and that is exactly as it should be. The nature of the game is such that a lot rides on a moment. We should therefore try to eliminate the DRS errors to the extent the human-technology interactions currently allow us to.

That said, the question whether greater certainty in decision making can come only at the cost of slowing down the game remains. Could the proposed changes take the joy out of the spectacle? They potentially could, but not if the ICC really think through how the different components of the DRS interact with each other. In fact, it is possible to not only improve the accuracy of decisions, but also simultaneously save time, add drama, and enhance the balance between bat and ball. Five components of the DRS appear to be particularly critical in this regard: umpires, no-ball decisions, line decisions, Hot Spot and player behaviour.

If the current technology leads to accurate predictive paths 93% of the time, the solution is to alter the dimensions of the stumps during TV replays by 7%. If a ball is then predicted to kiss the stumps, it would be a kiss of death.

Umpires: The simple fact is that human faculties are not equipped to accurately sense the sorts of things that umpires are expected to adjudicate on. Umpires get a vast majority of their decisions right primarily because of an intuitive feel for the game acquired through hundreds of hours spent making decisions. But concentration lapses can interfere in a big way. To overcome this problem, the four ICC-nominated umpires for each game could rotate among themselves and remain fresh throughout the five days. Ideally, an umpire should be given an hour's break after every two or three hours of officiating. The on-field umpires should also be given pocket monitors to view the replays during the review process. To involve spectators and for greater transparency, the ICC should permit TV studios to telecast audio feed of the umpires conversing with each other during the review process.

No-ball decisions: The need to monitor no-balls means that the umpires must, for a fraction of a second, focus away from the main area of impending action. To overcome this, cricket should consider adopting the electronic line judge used in tennis, which may require a second crease line about 12 inches further away and parallel to the popping crease. No part of a bowler's foot would be allowed to touch the front line (i.e. the line closer to the batsman). A touch would set off a 'no-ball beep' and give more time to the batsmen to react than is normally the case. Though this rule would result in the taller bowlers (those with shoes larger than 12 inches) bowling a bit behind from where they currently bowl, and the shorter bowlers gaining a couple of inches, which should not make any material difference. The back foot no-ball law could be done away with because it is not clear what advantage the bowlers gain by cutting the return crease. Further, waist-high and head-high no-ball calls could be delegated to the third umpire. This would involve factoring in each batsman's height while using the ball-tracking software. And since most of the dismissals require a no-ball re-check, automating no-ball calls would eliminate a large number of replays.

Line decisions: Altering other line decisions could also save a lot of time and facilitate decision making. The ball should remain in play until it touches the boundary line, the coordinates of a fielder's body should not really matter. To prevent a six however, fielders should be expected to remain within the boundary line while trying to keep the ball in play. This would mean making it essential to have a static boundary line. A movable rope would be unacceptable. The current law on catches on the boundary line is a sensible one and should be left untouched. The line laws pertaining to stumpings and run-outs too could be made more television-friendly. The line demarcating the crease should belong to the batsman. It is so much easier to see whether the foot or the bat is on the line than it is to ascertain whether some part of it is inside the crease. Once a batsman has dived to complete a run by touching the line or some part of the crease, the run should be deemed complete. Bat being in the air thereafter should not matter (provided the batsman is in the act of completing the dive and not turning for a second run). Some balance could be restored by ruling that direct hits would not result in overthrows.

Hot Spot: Hot Spot seems to be highly error prone and is known to be susceptible to weather conditions. One wonders whether it might be possible to wrap or spray the bat with materials that make the thermal signatures more visible. Such an approach could prove very cost effective and make Hot Spot decisions less controversial. Generally speaking, sound should not supersede Hot Spot's verdict. Audio signals can be misleading. The woody click from an errant shoelace once prevented Rahul Dravid from asking for a review. It took an observant Shane Warne in the commentary box to spot the culprit.

Player behaviour: In a recent article, Sambit Bal makes a case for demanding honesty from the players. Some of his ideas could be formally captured in an honour code that should, among other things, expect: (i) batsmen to walk if they were certain about having nicked the ball and if the umpire (not the fielder) confirmed that the catch was clean, and (ii) fielders to immediately inform the umpire if they were unsure about the legality of a catch. The players could also be encouraged to take an oath at the start of play on each day pledging against involvement with bookies and use of performance enhancing drugs. Indeed, efforts to improve the DRS would not amount to much if the players were to lack integrity or if the technology was not administered by well-trained umpires and technicians.

While TV studios could continue owning and operating the DRS technologies, decisions about which pictures to use during the review process ought to be made by neutral match officials. Furthermore, an ICC-appointed technical committee could be tasked to develop minimum acceptable parameters for the various DRS technologies.

Admittedly, there is no such beast as a perfectly administered DRS. But as Simon Taufel said in his MCC Spirit of Cricket lecture, "The technology genie has been let out of the bottle and it's not going to go back in." We should now aim to tame the genie and ask it to grab for us those elusive fruits in the upper echelons. Trialling some of the proposed ideas in first-class cricket would be a good start.

If you have a submission for Inbox, send it to us here, with "Inbox" in the subject line