South Africa end up on the wrong end of a rain-rule farce in the World Cup

In the game against England, the World Cup newbies fell afoul of the new, supposedly fairer, rain rule

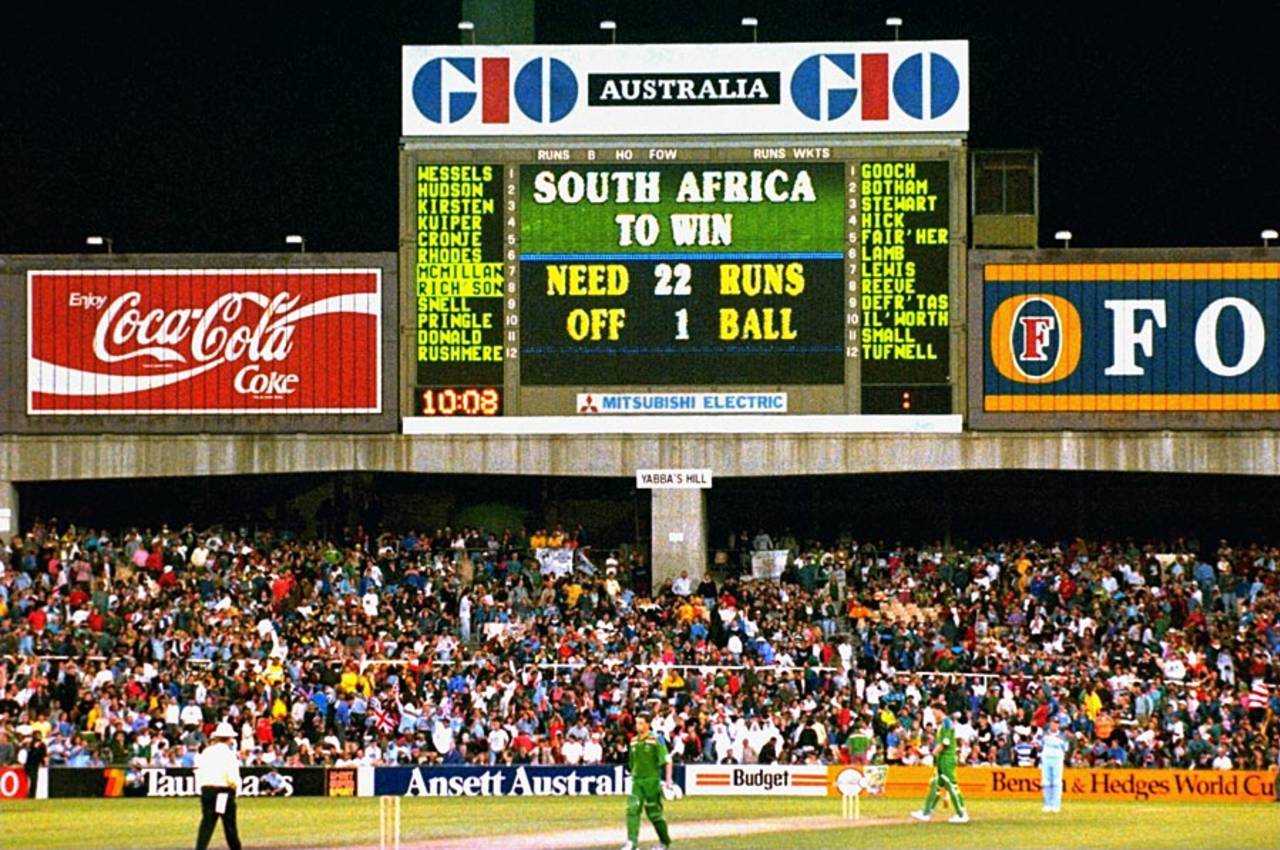

The scoreboard shows the absurdity of the conclusion to the England vs South Africa semi-final • Getty Images

The 1992 World Cup probably contained more innovations than any other. It was the first at which teams used coloured clothing, the first to use white balls (two at each end so they didn't get grubby), and the first to use floodlights. It also saw the introduction of a new rain rule. By the end of the tournament, the rule was utterly discredited.

The idea behind the rule was to avoid the old system - work out the runs-per-over of the first innings and then deduct that for each over lost by the side batting second - which heavily disadvantaged the side batting first. The solution, drawn up by experts including Richie Benaud, was that when rain interrupted the second innings of a match the reduction in the target was to be proportionate to the lowest scoring overs of the side batting first, a method that took into account the benefits of chasing, as opposed to setting, a target.

There were signs early on that all was not well. England bowled out Pakistan for 74 at Adelaide. The loss of three hours created a much stiffer target than the Pakistan batsmen had set. For the match to stand, a minimum of 15 overs had to be available to England; but as Pakistan's most successful 15 overs had yielded 62 of their 74 runs, under the rain rule the minimum target had to be 63. After a further shower it was set at 64 from 16, and England still needed 40 from eight when play was abandoned and the points shared.

But the nightmare became reality when England met South Africa in the semi-final at the SCG. England, put into bat by Kepler Wessels, scored 252 for 6 in their 45 overs, the innings curtailed as South Africa had bowled their overs slowly. They were fined for that, although as it turned out their actual punishment was far heavier than the monetary one.

South Africa's chase started well but then they lost their way until Jonty Rhodes got them back on course. With five overs remaining, they needed 47 to win, and that had been reduced to 22 from 13 balls when the rain, which had been falling for a few minutes, grew heavier.

The umpires, Brian Aldridge and Steve Randell, consulted and then spoke to the players. Brian McMillan and Dave Richardson, the South Africa batsmen, wanted to carry on. Graham Gooch was equally adamant that he wanted to come off as the England bowlers struggled with a wet ball and a sodden outfield. The umpires decided that conditions were unfit and the players were taken from the field.

Brian McMillan gestures at the umpire as the rain comes down•Patrick Eagar

Crucially, any time lost would result in overs being deducted, and under competition rules those would be the least productive for the side batting first. South Africa had bowled two maiden overs in England's innings, which meant that with 2.1 overs remaining any time lost would not result in a reduction in the target but would mean South Africa had fewer balls in which to score the runs.

The rain soon stopped and the total time lost was 12 minutes. It was announced that one over had been deducted and so South Africa's new target was 22 off seven balls. The news did not go down well with the 35,000 crowd and they reacted furiously, jeering and throwing rubbish onto the outfield.

The reality was even grimmer. The announcement of the six-ball reduction was incorrect. The Channel Nine commentators had been told of it by Allan Jordan, South Africa's manager, and in turn that was conveyed to the crowd over the PA. The ludicrousness was compounded when it was subsequently decided that the target was actually 21 as a leg-bye in one of the maidens had been overlooked.

The farce was still not over, however. The players trooped back to the middle unaware, like the crowd, that a second over had been deducted, and therefore only one ball remained. The players were then told, and the crowd looked on bemused as a scowling McMillan ambled a single and set off for the pavilion looking as furious as England - deserved victors, if truth be told - were embarrassed. A look at the scoreboard - which by then had been amended - led to more booing as reality dawned.

As if that wasn't bad enough, the scheduled finish time was 10.10 pm. The scoreboard clock was displaying 10.08pm. What's more, the competition rules had allowed for a reserve day but the host broadcaster, Channel Nine, had insisted the match be finished on the scheduled day.

To their credit, South African came onto the outfield to shake hands with the England side and then embarked on a lap of honour to warm applause from everyone, especially the England supporters.

"If I'd been in Graham's position I'd have done the same thing," Wessels said. "We had to bowl through semi-hard rain in their innings and didn't come off but England did. That's the umpires' decision. I can't do anything about this. I don't blame Gooch.

"It's unfortunate the England players got booed because it was no fault of theirs. It's just the rules."

South Africa complete a lap of honour at the end•Patrick Eagar

Gooch admitted he had used the rules to his advantage. "I'd be lying if I didn't think that maybe we should stay on," he said. "The South Africans must feel very dejected to lose like that and my heart goes out to them."

The organisers were, rightly, lambasted, although as John Woodcock in The Cricketer noted: "It must have been a source of great embarrassment to the organisers, though to the best of my knowledge they came nowhere near to admitting it."

In the Independent, Martin Johnson was typically forthright. "Had Martians landed at the SCG they would have concluded there was no intelligent life on earth and gone home." But he also laid the blame for their loss firmly at the feet of the defeated side. "The tears shed by non-South Africans last night would barely have filled an eggcup. Not only did they choose to bat second after winning the toss on a day that had blown in straight from Manchester but they also resorted to tactics that reassured us that the cynical side of South African sport has not disappeared after 22 years in isolation."

England went on to lose the final to Pakistan - a side who only made the semi-finals thanks to the point earned from that abandonment at Adelaide. As for the rain rule, it was quickly consigned to the dustbin and by 1999 the Duckworth-Lewis system, utterly confusing to the ordinary fan but studiously fair, had arrived.

Martin Williamson is a former executive editor of ESPNcricinfo