A champion of the players' cause

Tony Greig was one of England's premier allrounders and a man who didn't mind being villified for fighting for what he believed was his right

David Tossell

29-Dec-2012

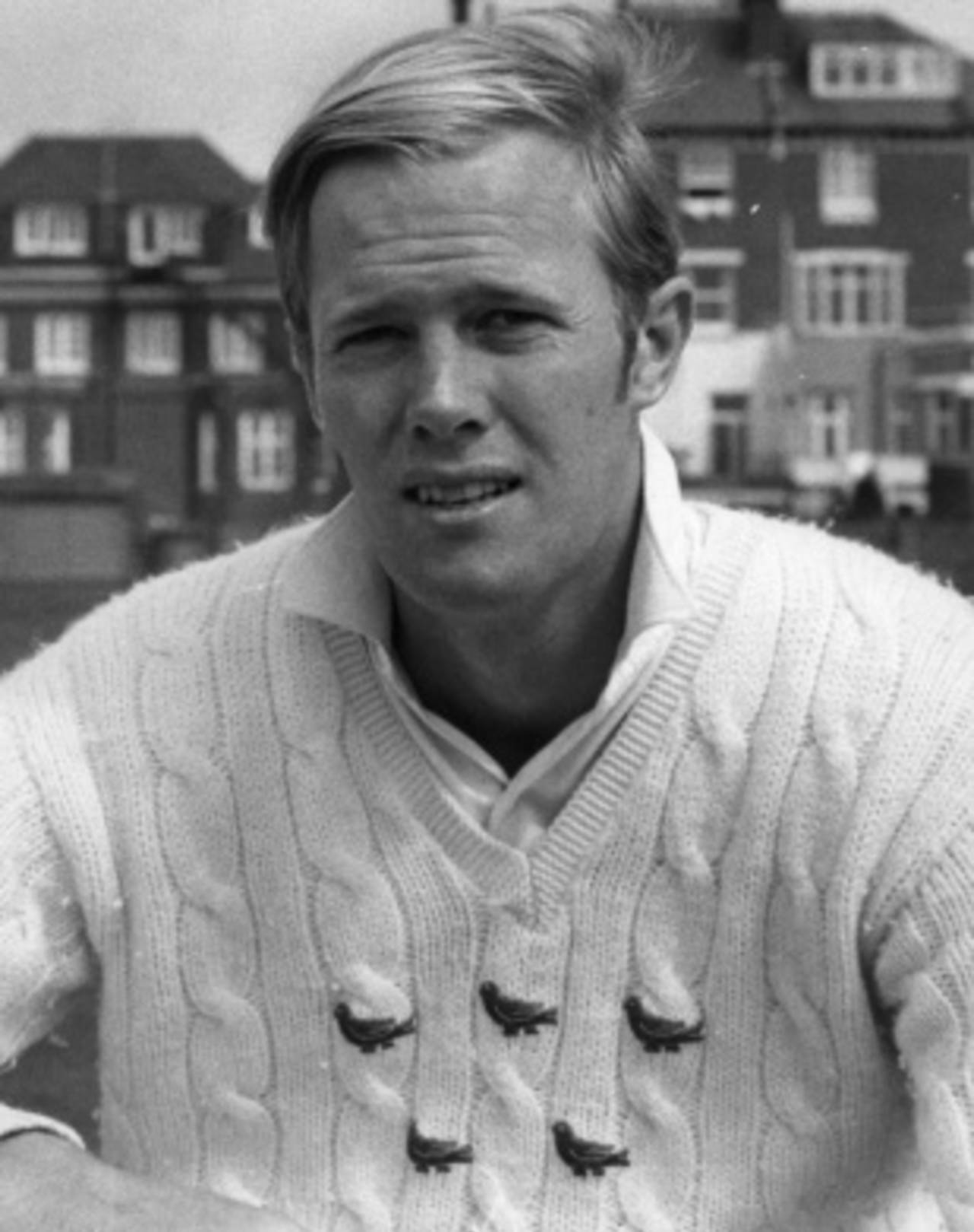

Tony Greig: not one to worry about what people said about him • Getty Images

With barely two of his enormous strides, Tony Greig crossed the Lord's hospitality box, into which his sister Sally Ann had invited me for tea, and stuck out his hand. "So," he said, smiling down in my direction, "have you sold all of those books of yours?"

It had been a year since publication of my biography of the former England captain, a project in which he had generously participated without there being anything in it for him. He had even offered to do some interviews "to create some headlines" in order to publicise the release date, and had duly taken swings at everyone from Dennis Lillee to the BCCI in the cause of publicity.

When I'd suggested he might want to see the book before helping to publicise it he'd responded: "I can't believe I wouldn't want it to do well." After the interview time, the family contacts and photographs, and the endorsements he'd given on my behalf to doubtful interviewees, this really was above and beyond the call of duty.

As we chatted now, guests of his brother-in-law, MCC president Phillip Hodson, while England and Australia fought out an ODI below us, I ventured the question to which I dreaded the answer: "You never did tell me what you thought of the book. Did you like it?"

"Well... I have to admit I haven't read it from cover to cover," he said, and in his reply was the implication that he'd probably read not a single word. It should have come as no surprise. Tony Greig, the South African-born captain who was accused of betraying English cricket, a man for whom controversy lurked at every turn of his career, had long since ceased worrying what people said about him.

Nor did he ever back away from the challenges that confronted him, whether it was the bouncers of Lillee and Thomson, Roberts and Holding, or the cricket authorities he defied by becoming a leading figure in Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket in 1977. It was why news of his death by heart attack early on Saturday as he fought cancer came as such a shock. If anyone was ever going to beat that most cruel of diseases, surely it was this greatest of competitors.

Born in Queenstown, South Africa, on October 6, 1946, Greig had a comfortable childhood, but it was never quite the idyllic upbringing that a white, professional family in the era of apartheid might have expected to offer.

That was due partly to the alcoholism that afflicted his Scottish father, Sandy, after a distinguished wartime RAF career that ended with his posting to South Africa as an instructor. Just as significant was the discovery, following Greig's collapse during a teenage tennis match, that he was epileptic. As a result, Greig began a lifetime of disciplined medication, keeping his condition from all but the closest of his team-mates over the years until acknowledging it publicly in 1980.

Sussex team-mate Peter Graves, one of those in the know, recalled the threat of an attack being a constant presence. "You always worried whether it was going to happen," he said. "Tony was like this juggernaut and he used to get really tired and that was when it could strike. He used to take a lot out of himself. But he wasn't a boozer and he wouldn't be up late."

Greig had arrived at Sussex in 1966, scoring a century against Lancashire on his Championship debut the following season. A striking 6ft 7in blond, he quickly established himself as an attacking middle-order batsman and purveyor of useful seamers off a jerky, pigeon-toed action.

Taking advantage of the opportunity denied his countrymen by South Africa's sporting exile but offered to him by his English residency and a British father, Greig won a place in the England team against the Rest of the World in 1970. The downgrading of that series meant it was not until the Ashes contest of 1972 that he played his first official Test, beginning an England career that lasted for 58 matches. During that time he dominated the team in a manner that few have done before or since.

His best performances were reserved for overseas tours, many of which are lost to cricket history due to the lack of TV coverage. On four consecutive tours - India (1972-73), West Indies (1973-74), Australia (1974-75) and India (1976-77) - Greig was England's outstanding player, proving himself Test cricket's pre-eminent allrounder.

It was not until 20 years after Packer that the MCC life membership traditionally afforded to former England captains came his way; not until the 2005 Ashes series that Greig was invited to commentate on a full England home series on a British station

In the Caribbean, he set up a series-saving victory in Trinidad by taking 13 wickets after deciding to try his hand at offspin. He'd already scored two centuries in the series and now, according to his great friend Alan Knott: "In that match he was the greatest offspinner I have ever kept to."

In Brisbane, in the first Test of England's disastrous Ashes defence, he thrashed 110 off Dennis Lillee and new fast-bowling discovery Jeff Thomson. When he wasn't deliberately upper-cutting Thomson over the slips, he was driving Lillee through the covers and celebrating by signalling his own fours.

His marathon effort in Calcutta two years later, when he defied India's spinners, the stifling atmosphere of an 80,000 crowd and a temperature of 40ºC, to score a match-winning 103, could not have been more different in character. "I have two memories that qualify Greigy as a top-quality player," said Derek Underwood. "The hundred in Brisbane and then the century in India against the best spin attack of all time. It shows that against any attack he was very high quality."

His Test batting average of 40.43, including eight centuries, and a bowling mark of 32.20 speak for themselves, placing him in the company of Ian Botham and Andrew Flintoff as England's great post-war allrounders. That he is not always acknowledged as such is because he was never a man of the people like "Beefy" or "Freddie" and that his exploits are not all over YouTube or retro TV sports channels.

Not to mention that two episodes as England captain tend to dominate popular memory of Greig.

Leadership of his country passed to Greig in 1975, in spite of reservations among those who felt his attempt to run out Alvin Kallicharran while stumps were being drawn at the end of play in the West Indies were indicative of an over-competitive nature unbecoming to the post.

When he announced on the eve of West Indies' visit in 1976 that he intended to "make them grovel" it wasn't just those dissenters who were outraged. Michael Holding remembered: "He was a white South African and 'grovel' was an offensive word for him to have used. It smacked of racism and apartheid."

As Holding and his team-mates made England pay with a brutal 3-0 series victory, Greig, who acknowledged immediately that he had made a clumsy choice of words, even went on his hands and knees in front of the West Indies fans at The Oval to do his own piece of grovelling.

Greig always knew how to charm. As Sussex and England skipper, he was accommodating to journalists - which could also be a source of trouble - and understanding of how to get the crowds on his side. Nowhere was that more evident that in his team's 3-1 win in India, where he praised the umpires, encouraged his men to play up to the stands, and walked away a hero.

Yet it was soon after that tour that his crown slipped, when it was announced that not only was he defecting to Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket, but that he had been busy recruiting players for the Australian tycoon in his battle against established cricket over TV rights.

Greig was no longer English cricket's saviour; he was a money-grabbing South African. Alec Bedser, chairman of selectors, was one of many who said Greig had "betrayed" his adopted country. When his children began getting abuse in the playground, Greig knew it was time to head permanently to Australia. His protestations that all cricketers would benefit were met by deaf ears and closed minds.

One of the first players to understand that he had a commercial value to be exploited, Greg said in later years that he went to WSC primarily for himself and his family, and secondarily because the cricket establishment needed shaking up. He saw that England players merited more than £210 per match and that county players deserved better than to work as shelf-stackers in the winter.

Within a year, Test fees were up to £1000. And when, only a couple of years after WSC, his brother Ian showed him his new contract offer from Sussex, which was more than he'd ever been offered even while captain of his county and country, he knew he had been vindicated.

Greig with his team-mates after winning the 1977 Ashes•PA Photos

Forgiveness took longer. It was not until 20 years after Packer that the MCC life membership traditionally afforded to former England captains came his way; not until the 2005 Ashes series that Greig - an established and typically controversial commentator on Packer's Channel 9 - was invited to commentate on a full England home series on a British station, Channel 4. It was completed earlier this year when he was asked to deliver the MCC's prestigious Cowdrey Lecture at Lord's.

No one who heard that predictably forthright speech knew that Greig's rehabilitation had come just in time; that a few months later he would be gone. He had seemed invincible.

He leaves a wife, Vivian, and four children, Beau and Tom, and from his first marriage, Mark and Samantha. And to cricket, cricket lovers and cricketers he leaves a legacy of defiance and brilliance; images of an upturned-collar and long-legged cover drives; and a debt of gratitude that every young professional in his sponsored car should acknowledge.

David Tossell is the author of Tony Greig: A Reappraisal of English Cricket's Most Controversial Captain, published by Pitch Publishing.